Inheriting an IRA is quite a bit different than inheriting any other asset. Unlike cash or investments in a traditional investment account, if you inherit an IRA you’ll need to start withdrawing from the account in order to avoid hefty penalties. In this post we’ll cover what your options are when you inherit an IRA, and how you can best manage it for you & your family.

How IRAs are Passed After Death

Whereas many of your assets will be distributed to heirs according to your will, IRAs are instead distributed by contract. Your custodian (the brokerage firm that holds your account, like Vanguard or TD Ameritrade) lets you designate as many beneficiaries and contingent beneficiaries as you like. Once you die, your account bypasses your will, the probate process, and is distributed according to this beneficiary designation.

When account holders don’t designate any beneficiaries things get a little murkier. When the account holder dies, their account is distributed according to their custodian’s default policy. At most custodians this default policy diverts the IRA back to their estate (and goes through probate) but at some it’s diverted to their spouse first. Unfortunately, if the account holder didn’t designate a beneficiary while they were alive, you’re at the mercy of your custodian’s policy.

If the account is indeed diverted back to their estate, it’ll be distributed according to your state’s interpretation of their will. And if they didn’t have one (meaning they died intestate), the state will make its own decision on who should inherit the asset.

The moral of the story? Take advantage of the opportunity to bypass probate, and designate your beneficiaries formally while you’re still alive.

Your Choices:

Remember that traditional IRAs are tax deferred. The U.S. government allowed the account holder to postpone taxation in order to save for their own retirement. That means that they haven’t collected any income tax on the contributions to the account yet.

It also means that when you inherit an IRA, the government is still waiting to tax the account. In fact, the IRS forces you to withdraw funds over time in order to collect their tax. Fortunately, you have several options surrounding how and when these withdrawals must occur:

The Life Expectancy Method

When you inherit an IRA, one permissible way to handle the account is to withdraw a certain amount of the funds every year for the rest of your life. Logistically, this means that you’ll transfer the funds into an inherited IRA, and start taking withdrawals by December 31st of the year following the decedent’s year of death.

For example, if you inherited an IRA today, in order to use the life expectancy method you’d need to take the first withdrawal by December 31st of next year.

The amount of the distribution depends on your life expectancy, which the IRS publishes (here) every year. The amount you’ll need to withdraw is the account balance on December 31st of the previous year, divided by your life expectancy from the “Single Life Expectancy Table” published by the IRS.

Here’s an example:

Let’s say you inherit a $100,000 IRA in June when you’re 45. To use the life expectancy method you’ll need to take your first distribution by December 31st of the following year, when you’re 46. If the account is worth $112,000 on December 31st in the year you inherited the account, based on the life expectancy table you’ll need to withdraw $112,000 / 38.8 = $2,887. You’ll then run the same calculation every subsequent year.

The 5 Year Method

Rather than spread the distributions over the rest of your lifetime, the 5 year method requires you to liquidate the entire account by December 31st of the fifth year after you inherit the account. This gives you more time to let the assets grow in the account, but also requires total distribution.

If you prefer the life expectancy method after inheriting an IRA but miss the first required withdrawal, you’ll be defaulted to the 5 year method. Since the life expectancy method will let the assets grow tax deferred for as long as possible, it’s important to make your decision as early as possible so you don’t miss the deadline.

Lump Sum Distribution

Finally, you always have the option of taking a lump sum distribution from the account whenever you like. This would save you from taking RMDs every year, but also foregoes any tax deferred growth. And, of course, you’ll pay income tax on the entire amount withdrawn.

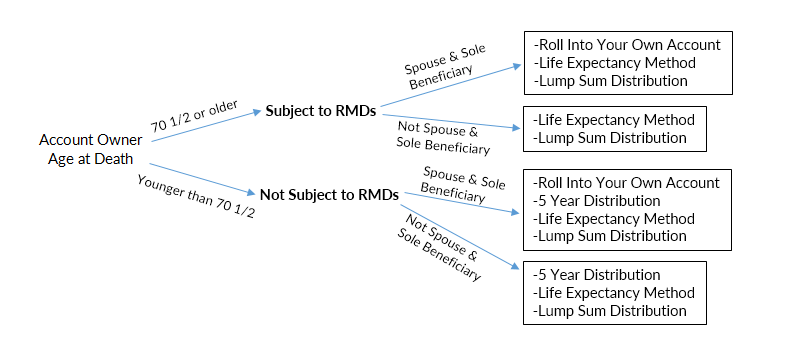

If the Account Holder Was Subject to RMDs

If the account holder was 70 1/2 or older when they died, you’ll need to make sure a required minimum distribution was taken. For example, if your husband died in January at age 75, you’ll still need to take the required minimum distribution for that year prior to December 31st. If you missed it, the dreaded 50% penalty would apply.

Your choices are different as well. You can still withdraw them according to the life expectancy method, but you won’t be able to use the 5 year liquidation rule. Since the account was already subject to RMDs when the original holder died, you’d need to continue them according to your own life expectancy. Or, of course, you could always take a lump sum distribution.

Spouses vs. Non-Spouses

If you inherit the account from your spouse as the sole beneficiary, you have an additional choice. You can actually transfer the funds into your own IRA and treat them as your own. This could be into an existing account or one that you open just for this purpose. In doing so, you’d be subject to the same early withdrawal and required minimum distribution rules as if it were your own IRA.

Here’s a primitive looking flow chart I cobbled together in excel:

Disclaiming an Inherited IRA

You can also turn down an inherited IRA. By disclaiming the inheritance you basically refuse to accept it. Some people prefer this route if they don’t need the money and are in a high tax bracket.

When you disclaim an inherited IRA, the asset is usually treated as if you’d died before the decedent (the account holder who died). That means that the IRA would simply go to the next person in line.

Since IRAs are distributed according to a beneficiary designation, your share would be split pro-rata among the remaining beneficiaries.

Here’s an example:

Let’s say that John is 75, a widower, and has two adult children. He has an IRA worth $100,000. He’s designated his children as equal beneficiaries of his account: each child is to receive 50% upon his death.

If he died, both children would inherit $50,000. But if child A were well off and decided to disclaim in the inheritance, child B would receive the entire $100,000.

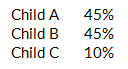

Now for a more complicated situation. Let’s say there are three children in the picture. John has good relationships with children A and B, but things are “complicated” with child C. He’s listed the following on his beneficiary form:

If child A disclaims his inheritance in this situation, the remaining funds would be distributed between the remaining siblings. With children B and C’s total combined share of the original inheritance being 55%, Child B would receive 82% of the inheritance, and Child C would receive 18% (45 is 82% of 55, 10 is 18% of 55).

If There are No Co-Beneficiaries

If there aren’t other beneficiaries to disclaim the assets to, the account is treated as if there were no beneficiaries listed at all. Like we addressed above, that means that the custodian’s default policy will apply. The funds may be diverted to a surviving spouse, or back to the decedent’s estate. In either case, before you disclaim an inherited IRA make sure you know who would be next in line to receive it.

Inheriting a Roth IRA

Contrary to popular opinion, inherited Roth IRAs have the exact same distribution rules as inherited traditional IRAs. The only difference is that you won’t pay any income tax on the distributions.

If you inherit a Roth IRA from your spouse, you can transfer the funds into your own Roth IRA. You’d treat the funds like your own – just as you would with a traditional IRA.

As a non-spouse, you’ll still be subject to either the 5-year liquidation rule or annual distributions across your lifetime. Most people who don’t need the money immediately choose to stretch out the distributions across their lifetime, since it allows the assets to grow tax free for longer. Even though you won’t owe any tax on the withdrawals, once you take the money out you’ll owe taxes on subsequent gains or distributions.

Still have questions? Feel free to leave them in the comments below or reach out to me directly.