“I’m not sure I have enough saved up to retire.”

“How can I know for sure my savings will last after I stop working?”

“I”m concerned I’ll spend through my savings too fast and run out of money when I’m 80.”

These are a few common phrases I hear from people who are approaching retirement. Many people I speak with in the their mid 50s and early 60s these days have saved diligently for years for their own retirement. But now as they approach the transition from accumulating wealth to spending their savings, the question of whether they’ve saved enough becomes extremely important.

Plus, when you mix in longer life expectancies, rising health care costs, and expensive stock and bond markets, there’s a lot of uncertainty surrounding the issue.

So in today’s post, I’ll cover some of the leading ways you can determine whether you have enough saved up to stop working. Without putting you and your family’s future at risk, that is.

How to Tell Whether You Have Enough Money to Retire

Financial and retirement planning really is both an art and a science. We all have a unique relationship with money. Understanding your experiences with and feelings toward your personal finances falls more on the “art” side of the spectrum. This is a crucial part of the equation, because our thoughts and feelings about money greatly affect how we make decisions.

I try to mix up art and science focused posts on the blog, but today’s will be more “science-y”. There are a couple variables at play when trying to determine whether you’ve saved enough to retire:

- Your total savings

- Your total guaranteed income

- How much you expect to spend

- How long you expect to live

- The expected rate of return on your investments

Basically, the objective here is to figure out how much you’ll need to withdraw from your savings each year in order to live in retirement.

This includes your expected spending, but is reduced by any guaranteed income you have coming in like Social Security or a pension. For example, if you think you’ll need $5,000 per month throughout retirement but have $3,000 in monthly Social Security and pension benefits, you’ll only need to pull $2,000 per month from your investments.

This amount is known as your retirement income gap. It’s the amount of monthly income that you’ll need to convert your retirement savings into.

Keep in mind that your retirement income gap may widen over time, thanks to inflation. If you think your initial monthly spending will be $5,000 after you stop working, that number will obviously increase over time with inflation. Whereas Social Security will offer cost of living adjustments to account for inflation, many pension benefits do not (you could also argue that cost of living adjustments don’t fully cover the actual increase in your cost of living).

Here’s an Example:

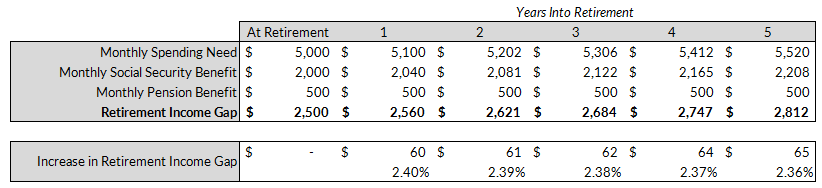

For example, let’s say that your spending needs increase at 2% per year thanks to inflation. You plan to collect Social Security benefits of $2,ooo per month, and a pension of $500 per month. Let’s assume the cost of living adjustments (COLAs) from your Social Security benefits boost your monthly check by 2% each year, matching inflation. But, let’s also assume that your pension benefits do not. Instead, they’ll remain flat at $500.

Even though inflation is only causing prices to rise 2% per year, your retirement income gap is growing closer to 2.4% per year.

[Click here to download Above the Canopy’s Retirement Readiness Checklist]

The 4% Rule

The next step is figuring out how much of your savings you’ll need to withdraw over time – expressed as an annual withdrawal percentage. So, if you need to withdraw $5,000 per month to live after you stop working and have saved $2,000,000 for retirement, your withdrawal percentage would be:

$5,000 * 12 = $60,000 / $2,000,000 = 3% per year.

This is where the 4% rule comes into play. There’s a good chance you’ve heard of the 4% rule before. It was introduced by a financial planner named Bill Bengen in the ’90s. Mr. Bengen had a good number of clients who were approaching retirement, and he wanted to make sure they’d saved enough before they stopped working. So, he used historical market data to calculate the maximum safe withdrawal rate for each 30-year retirement period starting in 1927.

In other words, he determined the highest annual percentage someone retiring in 1927 with a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds could withdraw each year, without ever running out of money. He then ran the same calculation for someone retiring in 1928, 1929, and so on until he ran out of data.

Unsurprisingly, he found that a 4% withdrawal rate worked in every single retirement period. The withdrawal rate in most periods was far higher than 4%, but the one that worked in every single scenario was 4%. Thus, his conclusion that if your annual withdrawal percentage is below 4%, you have enough saved up to retire.

I won’t rehash his entire findings here, but you can read more about the 4% rule in a previous post:

The Trinity Study

So what does the 4% rule mean for you? Based on Mr. Bengen’s work, if you’re retiring today, have a portfolio invested 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds, and live another 30 years or less, you’ll be just fine if your annual withdrawal rate is 4% or less. That is, of course, if the markets behave over the next 30 years just like they have since 1927.

While the 4% spending rule is a pretty helpful benchmark, it’s also a little rigid. What if you’re retiring early or late? Or what if you’re a conservative investor and prefer a bond-heavy portfolio? What’s a safe withdrawal rate in these circumstances?

These are the exact questions a group of researchers at Trinity University sought answers to in a 1998 paper. Using the same methodology as Mr. Bengen, the professors expanded on his hypothesis to determine portfolio “success rates” across a variety of time periods. Whereas Mr. Bengen aimed to find the one withdrawal rate that worked in each time period, the professors were more interested in testing success rates of different portfolios across different time periods.

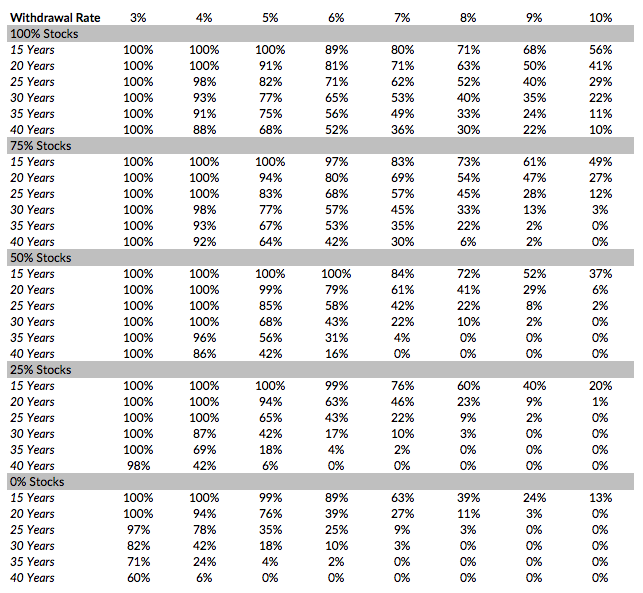

For example, let’s say you love your work and don’t plan to step away from it until you’re 75 years old. Doing so would shorten your retirement period, perhaps even to 15 years. Given the shorter retirement period you could probably bump up your withdrawal rate quite a bit and be just fine. In the Trinity study, the professors actually calculated the percentage of 15-40 year retirement periods using withdrawal rates from 3% to 10%.

The Trinity study was originally published back in 1998. But since then we’ve had some significant things happen in the markets and the economy:

- The dot com bust in 2001

- The mortgage crisis and great recession

- Ultra low interest rates and quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve

Because of this, several researchers have taken the reins and published their own updates to the study. With more market cycles and more financial data at our fingertips, researchers have more firepower to use when determining how much of their portfolio retirees can safely withdraw each year.

Here are the findings from one of Wade Pfau’s updates from 2014, who I’ll cover here shortly:

Source: Wade Pfau, RetirementResearcher.com

The data above incorporates market returns and inflation adjusted withdrawal rates from 1926 up until 2014. I should also note that Mr. Pfau’s research, like Mr. Bengen’s original work, used intermediate term government bonds as the bond benchmark. The original Trinity study used high-grade corporate bonds instead. And due to the asset class’s volatility, success rates were slightly lower than when intermediate term government bonds were used.

Wade Pfau

Wade Pfau has done a lot of interesting research on retirement, beyond his updates to the Trinity study. Mr. Pfau is a PhD and professor at the American College, and isn’t convinced the Trinity study and 4% withdrawal rule are even applicable to today’s retirees.

He claims there are a few reasons for this. Both the Trinity study and the 4% withdrawal rule are based on backward looking research. They both use about 90 years worth of data (the recent updates do, at least) from 1926 to today. This period covers a pretty wide swath of economic and market cycles. Since 1926 we’ve had:

- The great depression

- WWII

- Economic stagnation in the 1970s

- High inflation in the 1980s

- The stock market crash in 1987

- The aforementioned dot com bust, mortgage crisis, and great recession

But even though this time period covers a variety of market cycles, Mr. Pfau isn’t so sure the next 90 years in the markets will resemble the last 90 years. During the last 90 years, the U.S. became the world’s leading economic superpower. Since World War II our country has burst onto the scene with monumental economic growth.

Today, we’re fighting to preserve our position. The U.S. still has the most diverse, resilient, and powerful economy in the world. But the boom that brought our country to economic prominence over the last 90 years may well be behind us.

For today’s retirees, that could very well mean lower investment returns in the future. Mr. Pfau believes that today’s extremely low interest rates expensive stock markets makes the 4% withdrawal rule too risky. In other words, with potentially lower investment returns over the next 30-50 years, withdrawals of 4% from your portfolio each year might just be too much.

So what is a safe withdrawal rate?

Mr. Pfau suggests that 3% is a better place to start. Since today’s retirees are faced with pretty significant sequence of returns risk (due to expensive stock and bond markets) Mr. Pfau believes a 3% withdrawal rate gives you a sufficient margin of safety.

So Do You Have Enough Money to Retire?

All in all, the moral of the story here is that everyone needs an income plan as they approach retirement. If you plan to withdraw less than 3% from your retirement savings each year to live, you should be in pretty good shape. If your withdrawal rate is higher, you may want to look a little closer or consider getting a second opinion from a professional.

The moral of the story here is that everyone needs a customized retirement income plan. One of my favorite quotes from Mr. Pfau is his take on how people should interpret his research:

“People shouldn’t spend more time shopping for a vacuum cleaner than they do on their own retirement income plan.”

Retirees are living longer these days. And with uncertain investment returns and various living expenses (think healthcare) rising rapidly, there are a lot of moving parts to consider.

If you need some help developing your own retirement plan, feel free to reach out. I’m happy to point you in the right direction.

[button href=”http://abovethecanopy.us/contact/” primary=”true” centered=”true” newwindow=”false”]Contact Info[/button]